Last updated: January 12, 2026

A gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer is not just selling “cold.” They are selling predictability—so your shipments stay inside the temperature range your product needs, even when real life adds delays. Many teams align internal SOPs with simple food-safety references like keeping refrigerators at 40°F (4°C) or below and freezers at 0°F (-18°C) or below, while avoiding the 40°F–140°F danger zone when applicable.

If your outcome changes based on who packed the box, your system is not ready to scale.

This guide will help you answer:

- How to qualify a gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer with proof, not claims

- What specs prevent slow sampling loops and wasted pilots

- What “good” sealing and leak control looks like at scale

- How to judge thermal curves (and spot hidden spikes)

- How to build a pack-out SOP your team can repeat under pressure

- When to consider gel coolant packs vs dry ice for perishable goods

How do you pick a gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer fast?

Direct answer: Choose a gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer by demanding three proofs: raw thermal curves, leak-control records, and lot traceability. If any one is missing, you are gambling on scale.

Expanded explanation: Perishable shipping usually fails in patterns. A staging delay, a hot doorstep, or a corner air gap will cause the same failure again and again. The right manufacturer helps you break those patterns with documented controls and repeatable testing.

The PROOF-3 email you can send today

Ask every gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer for:

- Raw time–temperature curves for at least one realistic pack-out

- Leak-test routine plus one example record page (any lot)

- Lot code example on cartons, plus how complaints map to lots

| Proof you request | What you should receive | Red flag | What it means for you |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal curves | Raw time series + sensor map | “Passed 48 hours” only | Spikes stay hidden |

| Leak control | Freeze–thaw + seam checks | “Rarely leaks” claim | Wet cartons later |

| Traceability | Lot on cases + matching docs | No lot code on cartons | Slow root cause |

Practical tips and suggestions

- Test the lane that worries you most first.

- Require documented starting conditions; conditioning changes outcomes.

- Avoid one-sensor reports; corners and top zones often fail first.

Practical case: A team avoided a peak-season failure by spotting a late spike on raw curves and fixing placement.

What should you demand from a gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer?

Direct answer: Demand stability controls: tight weight tolerances, written seam acceptance rules, freeze–thaw leak stress checks, and clear change control.

Expanded explanation: Most failures come from seams, corners, and underfilled packs. You do not need a perfect factory. You need a factory that measures the right things consistently and can show records.

SEAL + SCALE: the QC checklist that predicts reliability

Ask your gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer to confirm these controls:

- Weight tolerance (min/max) and sampling frequency

- Seam acceptance criteria (what is a reject)

- Freeze–thaw leak stress method and frequency

- Lot traceability on cases and documents

- Change control for film, gel formula, or tooling changes

| QC control | What you ask for | What “good” looks like | Your practical benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight control | Lot min/max log | Tight range per lot | Predictable cooling |

| Seal control | Visual + stress routine | Recorded checks by shift | Fewer leaks |

| Freeze–thaw | Stress test method | Repeatable procedure | Real handling resilience |

| Change control | Notice + approval flow | Written policy | Fewer surprises |

| Traceability | Lot codes + docs | Lot visible on cartons | Faster containment |

Your quick “receive-and-hold” rule

- Ask for one QC record page before ordering samples.

- Tie inbound checks to lots to reduce disputes.

- Set a simple hold rule: if seams seep, quarantine the lot.

Practical case: One operator reduced wet boxes by adding a receiving gate and rejecting a drifting lot early.

What specs should you send a gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer?

Direct answer: Send a one-page spec that defines the temperature job, duration, internal shipper size, payload mass, and worst-case exposure.

Expanded explanation: “We need gel packs for perishables” is not a spec. It hides insulation, void space, staging time, and last-mile heat. A measurable spec turns sourcing into engineering and makes pilots comparable.

Your one-page spec (copy and fill)

- Product type: seafood / meal kits / dairy / produce / flowers / other

- Temperature band: chilled / frozen / protect-from-heat

- Target duration: 24 / 48 / 72 / 96 hours

- Worst-case exposure: hot truck + doorstep dwell + staging delay

- Shipper internal size (L × W × H)

- Payload mass and placement

- Max added weight allowed

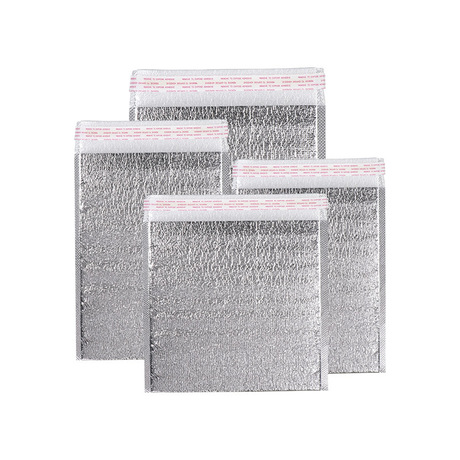

- Pack format preference: panels / bricks / pouches / mixed

- Pass/fail: “Payload stays within target band for __ hours.”

How to write a pass/fail rule that avoids disputes

- Keep it one sentence, not a story.

- Mention time and the temperature band your product needs.

| Pass/fail style | Example | Why it works | What you avoid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chilled | Stays chilled for 48 hours. | Clear, time-based | Endless debate |

| Frozen | Arrives solidly frozen at 60 hours. | Outcome-based | Misleading averages |

| Heat protection | Stays below our limit for 24 hours. | Matches the job | Overcooling mistakes |

Practical tips and suggestions

- Always use internal shipper dimensions; outer dimensions mislead placement.

- Set a weight ceiling to control cost and simplify trade-offs.

- Include staging time; it is often the hidden failure driver.

Practical case: A team shortened sampling by locking one shipper size and one pass/fail sentence.

How do you validate thermal curves from a gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer?

Direct answer: Demand raw time–temperature curves with setup notes, multiple sensor locations, and repeat runs. A single pass/fail summary is not enough.

Expanded explanation: Perishables often fail during short spikes near delivery. You need a curve you can trust and a method you can repeat. In parcel lanes, proof-first qualification is increasingly common, and your drafts explicitly reference ISTA STD-7E as a parcel thermal testing standard used for comparable profiles.

The 6 items every test report must include

- Conditioning method (time and setpoint)

- Payload mass, layout, and starting temperature

- Shipper insulation and closure method

- Sensor map with at least three locations

- Ambient profile description (mild and hot)

- Raw time-series data plus a short narrative

The “Start–Transit–Arrival” curve check

Use three checkpoints:

- Start: does it stabilize quickly after packing?

- Transit: is the mid-window steady?

- Arrival: does the last window spike or collapse?

| What you see | What it suggests | Typical cause | First improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong transit, weak arrival | Doorstep risk | Top exposure or slow closure | Add top protection, close faster |

| Warm corner drift | Uneven coverage | Gaps or movement | Improve fit and anchoring |

| Early swings | Packing variation | Air gaps, slow steps | Simplify SOP, reduce choices |

Practical tips and suggestions

- Ask for two runs on different days to confirm repeatability.

- Include a staging-delay scenario in at least one pilot.

- Use curve shape, not averages. Short spikes are expensive.

Practical case: A team improved results by tightening placement and reducing void space without adding packs.

How do you build a pack-out SOP that your team repeats?

Direct answer: A repeatable SOP removes choices: fixed placement, fast closure, and a seasonal upgrade that keeps the same steps.

Expanded explanation: Most thermal failures are packing failures. Air gaps, movement, and slow closure erase your buffer. The best SOP is not the most clever. It is the one your team repeats perfectly.

PACKED: a simple method your team can remember

- P: Place packs first (anchor before payload)

- A: Avoid air gaps (reduce voids and movement)

- C: Close quickly (trap cold air)

- K: Keep it simple (one or two pack sizes per shipper)

- E: Execute with photos (visual beats text)

- D: Document lots (lot codes tie outcomes to batches)

Layout patterns that scale

| Layout | Where packs go | Best for | Why it works |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frame | Four sides | Mixed perishables | Even coverage |

| Cap | Top + two sides | Hot last mile | Protects the arrival window |

| Cradle | Bottom + sides | Heavy payload | Reduces warm-up from below |

Perishable Lane Stress Score (interactive)

Score each item 0–2 and add them up:

- Transit uncertainty: none (0), some (1), high (2)

- Outdoor exposure: shaded (0), mixed (1), direct heat (2)

- Staging time: short (0), medium (1), long (2)

- Shipper void space: low (0), medium (1), high (2)

- Packing variation risk: low (0), medium (1), high (2)

Interpretation:

- 0–4: base pack-out may work

- 5–7: add a cap layout or increase insulation

- 8–10: design a hot-lane upgrade with more thermal mass and stricter SOP

Practical tips and suggestions

- Standardize one placement rule before you change pack count.

- Remove movement before you add more thermal mass.

- Train with a photo card at the packing station.

Practical case: A team improved summer performance by switching to a cap layout and reducing air gaps.

Gel coolant packs vs dry ice for perishable goods: how do you decide?

Direct answer: Choose the simplest refrigerant strategy that meets your promise. Dry ice can extend frozen protection, but it adds handling, labeling, and workflow complexity.

Expanded explanation: Many teams switch to dry ice when the real issue is poor top coverage or too much void space. Your drafts also note dry ice markings that often include “UN1845” and net weight in kilograms in acceptance-style checklists.

Decision tool (yes/no)

Answer yes or no:

- Do you need fully frozen delivery after long, hot exposure?

- Do you have trained staff and clear labeling workflows?

- Can your packaging vent appropriately for dry ice?

- Do carriers accept your dry ice workflow consistently?

- Is your gel system failing only in extreme lanes?

Interpretation:

- If yes to 1–4: dry ice may fit

- If no to 2 or 4: optimize gel pack-outs first

| Option | Strength | Operational load | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gel coolant packs | Simple SOP | Low–Medium | Most chilled lanes |

| Higher-mass gel packs | Bigger buffer | Medium | Hot-season upgrades |

| Dry ice | Strong frozen margin | Higher | Long, hot frozen lanes |

Practical tips and suggestions

- Don’t add complexity too early; fix geometry and SOP first.

- If you use dry ice, standardize labeling steps and training.

- Track failures by lane and season to choose the right upgrade.

How many gel coolant packs do you need for perishable goods shipping?

Direct answer: There is no universal number. Pack count depends on shipper size, insulation, payload mass, exposure, and cold start conditions.

Expanded explanation: Most teams overpack because pack count is easy to change. But the first wins usually come from better fit, less movement, faster closure, and improved arrival protection. Use a pilot-based method so every change teaches you something.

The Pack Count Reality Check (quick self-test)

Answer yes or no:

- Is your box mostly full (low air volume)?

- Do packs touch inner walls consistently?

- Can your team pack the same layout in under 60 seconds?

- Does your design protect top and corners?

- Do you control staging time and closure speed?

If you answered “no” to two or more, fix geometry and SOP first.

A pilot plan that avoids random tuning

| Pilot step | What you change | Why | What you learn |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot 1 | Baseline layout + baseline packs | Establish baseline | Typical curve shape |

| Pilot 2 | Same layout + hotter exposure | Stress test | Arrival window behavior |

| Pilot 3 | Same layout + top protection | Fix late spikes | Doorstep resilience |

| Pilot 4 | Same layout + reduced void space | Reduce variation | Repeatability improvement |

2026 trends that matter for a gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer

In 2026, your drafts highlight three shifts:

- Proof-first qualification is becoming standard, including parcel thermal testing references like ISTA STD-7E.

- Temperature discipline is tightening, with more teams aligning SOPs to basic safety references.

- Compliance-style handling is spreading beyond pharma into premium food operations.

Latest progress at a glance

- More raw data sharing: curves, sensor maps, repeat runs

- More seasonal playbooks: mild and hot configurations with the same steps

- More lot accountability: lot codes, receiving QC gates, and change control

Market insight: the best gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer behaves like a systems partner, not a commodity supplier.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How do I choose a gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer fast?

Ask for raw thermal curves, leak-test records, and lot traceability. Then pilot the worst lane before scaling.

Q2: What should gel coolant pack thermal testing for perishable goods include?

Starting conditions, sensor placement, ambient assumptions, and raw time-series data. Repeat runs improve trust.

Q3: How many gel coolant packs do I need for perishable shipping?

There is no universal number. Shipper size, insulation, payload, exposure, and cold start decide the answer.

Q4: What is the simplest leak test I can run on inbound packs?

Condition packs, press seams after slight thaw, wipe for micro moisture, and record results by lot code.

Q5: Why do some shipments fail only in summer?

Summer amplifies arrival risk and doorstep dwell. Improve top protection and reduce void space before adding pack count.

Q6: What labeling details matter for dry ice shipments?

Dry ice packages commonly need dry ice wording (or carbon dioxide, solid), UN1845, and net weight in kilograms in acceptance-style workflows.

Summary and recommendations

A gel coolant pack perishable goods manufacturer should deliver predictable outcomes through stable pack mass, strong seals, and lot traceability. Start with a one-page spec and request proof before samples. Pilot your worst lane with staging delay included, then lock a photo SOP and a quick receiving QC gate. Once stability is proven, optimize cost with fewer failures and smarter geometry—not by chasing the cheapest pack.

Action plan (CTA)

- Write a one-line pass/fail rule for your most important lane.

- Measure shipper internal size and document payload placement.

- Request raw curves, QC logs, and lot coding examples from two suppliers.

- Pilot the worst lane first, then lock a photo SOP and receiving QC gate.

About Tempk

We design cold chain packaging systems for perishable shipping that must work in real warehouses and real last-mile conditions. We focus on repeatable pack-out methods, validation planning, and receiving QC routines that teams can run quickly.

Next step: Share your shipper internal dimensions, temperature band, target duration, and worst-case exposure. We’ll propose a pilot-ready pack-out concept and an acceptance checklist your team can deploy immediately.